Blog Post #1

– Elizabeth Ervin

Sometimes it can be hard for one person to make a difference in big public issues, but these suggestions illustrate how we can assist each other in finding strength in numbers.

The first chapter of Elizabeth Ervin’s “Public Literacy” strives to define public literacy not by establishing a limited definition, but through the examination of various questions and obstacles that once impeded and continue to impede the development of public literacy. Ervin herself stated that she had no desire to define public literacy for her audience in strict terms, but rather desired to start a discussion that prompted her audience to come to their own conclusions regarding what public literacy is and how it could be utilized within writing for the public.

“Defining Public Literacy: Five Dilemmas”

The five dilemmas explored by Ervin make up the bulk of her article. These dilemmas, she claims, are the main reasons why it is so difficult to define public literacy. They also connect back to her opening argument, which stated that “think[ing] about ‘public literacy’ is to plunge into a series of questions that have preoccupied readers, writers, thinkers, and citizens for centuries.”

The first dilemma requires differing between public and civic, the need for which is a fairly recent development. Civic is limited to publications which impact the workings or function of the government. For centuries, anything public, including entertainment, were also considered to play an important role in the development of culture, which impacted the civic. It is only recently that a gap has formed which necessitates the differentiation.

The second and third dilemmas revolve around diversity. Centuries before, it was safe to assume that anyone involved in the public sphere would have similar values and beliefs. Today, the world is so incredibly diverse that it is impossible to recognize a single public sphere. Instead, there are multiple public spheres with individuals often belonging to more than one sphere in order to account for the diversity in values and beliefs held by an incredibly diverse populace. To accommodate the increasing number of public spheres, an increasing number of platforms to publish to have been developed.

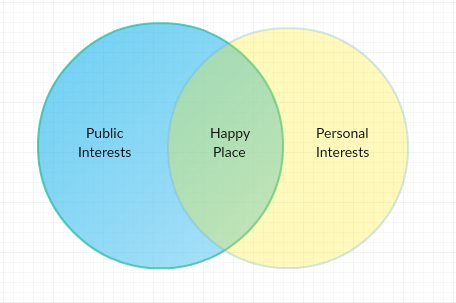

Dilemma number four discusses the venn diagram that is public and personal interests for when it comes to participating in the public sphere. Personal interests do not always match public interests, but the two are not mutually exclusive either. The fifth and final dilemma introduced in Ervin’s chapter discusses ownership of intellectual property and the position of public domains.

The Point

The word dilemma can be misleading. It tends to have a negative connotation and basically means there’s a problem. When Ervin calls these points mentioned above dilemmas, she is not arguing that they are wrong. The point of the chapter was to define public literacy. The dilemmas then, are simply points that make defining public literacy difficult. They are not difficulties that need to be swept away. Quite the opposite, in fact. Not everything needs to be for a purpose to the government, as long as the option to be involved with the government remains. Certainly increased diversity in both the number of spheres and the platforms available to them create countless unique conversations that all manage to connect to each other despite the differences. Finally, it is unfortunate that some people favor personal interest to public interest, but the whole point of public writing is to dissuade the notion that those in power are all-powerful and those not directly involved in a situation are powerless.

In other words, by attempting to define public literacy by examining the dilemmas involved with that task, Ervin makes the powerful statement that we have power in numbers. Anybody is capable of change, if only they have the proper tools. To Ervin, those tools include access to the public sphere. Sure, some people will use the public sphere to watch hours of adorable cat videos. The point is that others will use the public sphere to campaign for equal rights for the LGBTQIA community, or to inspire wide scale change in the school systems, or to get Netflix to keep Friends for another season.

The possibilities are endless.

Elizabeth Ervin managed to create a deceptively simple article which appeared to define public literacy by not defining public literacy. Rather than a simple definition, Ervin summed up the history of public spheres in such a way that subtly lobbied for the importance of participation by anyone willing. Her stated goal was to lead her audience to becoming more effective at writing for the public by exposing them to ideas and letting them come to their own conclusions. Well, she did it.