A “Focus on Letters” Analysis and Review

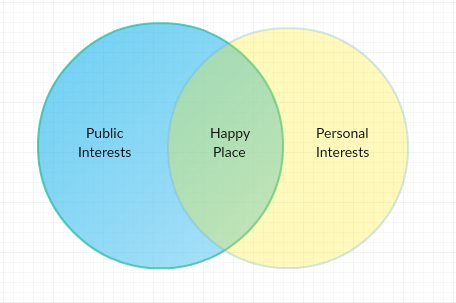

Elizabeth Ervin’s chapter six of Public Literacy is entitled “Focus on Letters.” As indicated by the title, the chapter focuses on various types of letters that can be utilized within the public sphere. Ervin identifies four forms of letters to be discussed in detail within her chapter: letters to editors, letters of concern, appeal letters, and open letters.

The majority of the chapter is dedicated to taking a closer look at what each type of letter can be used for and the general appearance it takes. Ervin explains that letters to editors can come in two forms, addressed to the editors or addressed to the editor’s audience, and that letters of concern should generally follow traditional business letter formats. She offers explanations for how a writer’s motivations effect a letter type, as well as an audience’s perceptions.

Ervin’s chapter “Focus on Letters” offers a lot of helpful information for writers who intend to engage in the public sphere through the utilization of letters. While she opens the chapter with the claim that she does not intend this to be a “how-to” guide for writing letters, she does offer up an abundance of information that can assist writers throughout the process. Getting started tends to be the hardest part, but her chapter can be used to determine which type of letter to work with and the form it should take. Overall, her chapter is meant as a really useful tool for writers intending to create a public literacy letter.

Public Literacy is intended to inform potential writers about how to engage in the public sphere with public literacies in all their various forms. While Ervin makes several claims throughout that she is not intending her work to answer specific questions or give step-by-step instructions, she still managed to create a helpful guide that, though it is not a “how-to” guide, offers enough advice and examples that it works to direct potential writers in their missions. Ervin’s chapter, “Focus on Letters,” is just one more form of public literacy that is outlined and explored in Ervin’s book. The sheer volume of public literacies can be overwhelming, but Ervin endeavours to break it down into manageable pieces that can be easily understood and utilized.

While Ervin does an excellent job of breaking down the four types of letters- letters to editors, letters of concern, appeal letters, and open letters- she almost keeps it too simple. For her purposes regarding Public Literacy, it is understandable that she wants to keep her chapters short rather than bogging them and the readers down with extra information that may muddle her point. However, with chapter six, “Focus on Letters,” Ervin makes mention of a letter type that did not make it onto her list of four letters. In her “Letters of Concern” section, Ervin makes brief mention of letters of complaint. She then fails to include any more information about it.

That in itself is not a huge concern, especially considering the amount of information she does manage to pack into her chapter. Nonetheless, it leaves me wondering how many other letter forms she neglects to mention or examine within her “Focus on Letters” chapter. Are there just one or two types that she did not feel were overly relevant, or are there countless that writers could be using within the public sphere that failed to make it onto her “examine closer” list?

Susie, what shall I do – there is’nt room enough; not half enough, to hold what I was going to say. Wont you tell the man who makes sheets of paper, that I hav’nt the slightest respect for him!