Reading Response #6: “Time in School: How Does the U.S. Compare?”

Jim Hull and Mandy Newport worked together to create a brief entitled “Time in School: How Does the U.S. Compare” which strives to answer the question do United States students spend less time in school than students in other countries? Published by the Center for Public Education, the article examines the claim made by U.S. Department of Education Secretary Arne Duncan during a congressional hearing which used data to assert that students in India and China attended school twenty-five to thirty percent longer than students in the United States. The claim was made in an effort to prompt a policy decision in favor of raising the minimum number of hours required by schools in the United States.

Hull and Newport’s article utilized data from the OECD (Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development), Education Commission of the States’, and the World Data on Education to develop the briefing. The time measurements were based on the countries’ compulsory hours, or minimum hours of instruction per year, allowing for some discrepancies in what countries consider instructional hours. India and China were considered to directly examine the claims made by U.S. Department of Education Secretary Duncan. Korea, Japan, Finland, Canada, England, France, Germany, and Italy were also examined in order to fully examine whether United States students were required to spend less time in schools than other countries.

The results were overwhelmingly against Secretary Duncan’s claims. India and China required less or about equal to the same number of hours as United States. The other countries repeated this pattern, often requiring less hours. Finland, one of the world’s top performers in education, actually had a minimum number of hours significantly smaller than the United State’s average and still less than Vermont’s minimum, which is the least amount of hours required of any state in the U.S.

As a work in the public sphere, this briefing is a well done response to claims made by a public figure. U.S. Department of Education Secretary Arne Duncan made a claim, and the authors of this briefing, Jim Hull and Mandy Newport, made a reply in that they looked at Secretary Duncan’s claims and determined more explicitly the veracity of said claims. The briefing remains unbiased, clearly listing the source of its data and the method utilized. It also makes clear the limitations of its findings. The briefing also offers alternative methods to be considered in order to improve student effectiveness that does not include adding more hours to the minimum requirement.

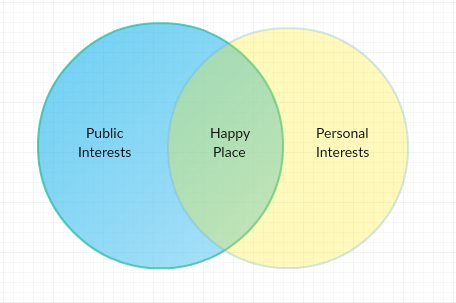

The article is interesting in that it puts the United States public schools on a national scale and makes a comparison. The United States is fairly average in number of instructional hours required of students. Increasing the minimum would not create a more constructive educational system. Making students attend school longer would not make them better students. Instead, policy makers should consider alternative methods to increase effectiveness of students and instruction. The briefing lists a few ways to make the most of school time. I would encourage ways the schools could make the most of the students’ abilities. Mental health issues have been proven to be detrimental to student success, especially when they present as behavioral issues that disrupt entire classrooms. By addressing these concerns through various practices designed to better the current treatment and counseling systems indirectly, students would receive the help they need and their balanced well-beings would result in more effective learning. Students with balanced mental health would be more successful and less distracting, resulting in the improvement of school effectiveness desired by policy makers such as U.S. Department of Education Secretary Arne Duncan.